- Themes discussed:

- Morality

- PTSD, Grief and Survivor’s Guilt

- Attachment Theory

- Defence Mechanisms

Needless to say, this post contains significant spoilers. The Last of Us is a masterpiece – do not let me ruin its story for you if you haven’t played it. Go forth and experience this truly unique adventure before reading this article.

The narrative design in The Last of Us is ascendant. I would not hesitate to cite it as the best written game of all time, if not for the portrayal of the characters therein. It is, in my opinion, the current pinnacle of storytelling in games, a feat it achieves through a raw and often painful observation of the human condition.

Whilst Ellie’s journey is more relatable, I find the arc through which Joel travels to be fascinating, moving, realistic and terrifying all in equal measures. It’s taken me weeks of research and analysis to even sit down to write his profile. I hope I can do him justice.

This article comes with a trigger warning for descriptions of very traumatic events which, though they are fictional, could be triggering. If at any point you need to stop reading, please do, and of course refer to your local mental health service.

Joel doesn’t give much away on the surface. He’s stoic, emotionally unavailable, and mercilessly practical. It is easiest to penetrate his psyche through his relationships with others; his behaviours around those close to him often betray his underlying motivations, which he would prefer to remain well hidden. Let’s do this chronologically.

When we construct a psychological formulation, we like to start right at the beginning. Think as far back as conception. We go forward from there and continually add data to get a better idea of how someone thinks and feels, what motivates them, what they fear and believe, and altogether who they are as a person.

Of course it is difficult to be thorough in most cases, because there are gaps, but we take what we can get. So what we know of Joel’s childhood revolves around his interactions with Tommy.

We are told that Joel basically raised his younger brother. It seems as though for whatever reason, there was a lack of reliable caregiving from the adults around them, and therefore Joel’s instinct to survive began very young.

Attachment theory describes how a person relates to others, specifically how much he feels able to rely on them.

The avoidant person feels, “No one will look after me so I have to look after myself (and people I love)”. He would therefore have an overwhelming sense of responsibility to those he loved, believing that no one else was capable of caring for them but him.

This is likely why, later on, Joel was willing to do anything he could to get by, including things he morally disagreed with – if it would keep him or his loved ones safe. Incidentally, this also contributes to a lot of Joel’s more admirable traits – his loyalty, his willingness to put others before himself and his persistence in the face of adversity.

Because Joel is such a secretive individual, he has not spoken directly about his wife. He mentions he had Sarah young – before university age, so likely around 17 or 18 seeing as Sarah is 12 at the start of the game. Perhaps this was during a rebellious phase, after many years of single-handedly caring for Tommy? If so, the entire marriage would be encompassed in significant guilt for the perceived abandonment of his brother, entangled with a similarly strong sense of responsibility over his spouse and, soon after, his daughter. This would be confusing and difficult to navigate for Joel, who has not learned how to express himself, having had no adults to show him how to.

What happened next? We’re not sure, but we can glean information from the environmental storytelling. We know Joel was raising Sarah since at least infancy (if not since birth). There are no photos of his wife in the home. We are not sure whether she died, or left abruptly. We do know the separation was painful (briefly explored later during a conversation with Ellie).

Either way, Joel was thrust into a situation where he had responsibility over someone else, again, in a thread that has yet to break. Interestingly, if we assume that she died, and there are no photos, that means Joel has been compartmentalising and ignoring the painful things in his life for a long time.

These events probably reinforced Joel’s need to be faultlessly independent, to never rely on anyone but himself, feeding back into that avoidant attachment style.

Single fatherhood probably suited Joel quite well. He is self-sufficient and selfless simultaneously; this would have come completely naturally, and in fact anything else might feel overwhelming.

By this point, we’re looking at a man who has spent his entire life looking after other people. There has never been space to explore who Joel is, and that likely suited him. Finding oneself is a psychologically complex experience, and this is a man who doesn’t even know what he is feeling most of the time, never having had adults to contain and normalise his childhood emotions.

Let’s skip forward to the opening of the game. What do we know about Joel?

The death of a child is unimaginably traumatic to any parent. I can’t even begin to comprehend what that loss would be like. To really understand what happened over the next twenty years, we need to look at this devastating event in context.

Within the first hour of the game, Joel is left without a daughter and without an identity. Everything he was would have revolve around Sarah. Protecting her was his only purpose, and losing her would have been literally unbearable.

Driven by adrenaline, unable to psychologically process what had happened, and fortunately led by his brother, I can’t imagine Joel even remembers what happened next. It isn’t until things calmed down a bit that he would have been able to truly reflect on what was left.

It is perhaps understandable that Joel would have considered ending his own life. For a man who puts unfaltering responsibility for the fate of others upon himself, it would feel like he had failed in the most absolute way. In real examples of similar situations, people often state they feel they deserve to die. Their instinct therefore to live, even though their loved one didn’t, causes them a deep anguish. This is called Survivor’s Guilt (a type of PTSD), and it is something that would plague Joel for two decades.

When Joel tells Ellie, “You have to find something to fight for,” he is referring to the journey he went on to justify himself wanting to keep living, when morally he believed that he should die.

Joel tends to pick one person at a time to look after. For a while, this was Tess.

Tess is a survivor, she is strong and independent too – she represents some respite for Joel from his role as sole protector. It seems for a while, he was able to give someone else some of the responsibility. That is HUGE for him, and allowing himself this was probably one of the only ways he was able to cope with the transition after Sarah’s death.

What else can we tell through Tess? The two clearly have a relationship that goes beyond practical.

It means he was able to let himself succumb to his basic human needs again, and to justify it to himself. He’s regaining some of what he had lost. In a way, he is using Tess for self-preservation.

And so, old habits dying hard, he becomes fiercely loyal to her, even going out of his way and doing things he doesn’t agree with to further her agenda, to protect her and ensure her safety (and therefore his own purpose). By the time she dies, she understands what this will do to Joel. Instead of allowing him to fall apart, she gives him one last mission – protect Ellie. And thus the chain continues.

If we pull an Inception and “go deeper”, by the game’s climax these two characters can be seen as metaphors for morality . Marlene represents utilitarianism – the ends justify the means, even if those means are obviously immoral. To Marlene, hope for the human race justifies ending Ellie’s life.

He is not the opposite of Marlene, ethically. That would be deontological ethics – that one must do what is morally right by the minority despite the consequences. Instead, he seems to act amorally, and knowingly so, to preserve himself. He knows what he is doing is wrong, and he doesn’t care. This is more a representation of psychological egoism, though my philosophy is not up to scratch so I’m happy to be corrected,

Ok, let’s start again from the begin and look at this journey chronologically.

Ellie is roughly the same age as Sarah was when she passed away, give or take a couple of years. Of course, the alarm bells go off immediately. He is incredibly slow to warm toward her – at times abrupt and even rude. I won’t get any awards for psychoanalysis by stating this is obviously because she reminds him of Sarah and he’s subconsciously trying to distance her and avoid painful reminders of his own loss. Poor Ellie doesn’t know this, but she is exceptionally resilient so she just keeps on persisting with him.

After Tess’ death, Joel is left with a burden he cannot refuse.

To preserve his own psychological stability, he must do what Tess asks him to, so that she hasn’t died in vain and he alleviate some of the guilt he feels for failing to protect her. That means delivering Ellie to the fireflies. The two remain together out of necessity, and thus begin to engage in a relationship that is like an elastic band – constantly fighting to be apart and coming back together nonetheless.

A lot of this psychological push-and-shove comes from the natural paternal relationship there, contrasting with Joel’s abject terror at having to feel…anything, really. However, despite his best efforts it is clear that by the time they leave Bill’s, he has developed a platonic affection for Ellie which he spends several months struggling to reconcile. He compliments her performance not once but twice, and even lets himself actually feel relaxed around her. You can see his guard melt away, slowly enough that he wouldn’t even notice. The riposte to this, of course, is far more swift when moments occur that remind him of what he stands to lose.

A key example of this happens not long after Tess dies. In order to save Joel from being violently drowned to death by an enemy soldier, Ellie shoots “the hell outta that guy, huh” saving his life – yet he scolds her. Why? It’s not because she put him in danger, as he suggests – but because she put herself in harm’s way for him.

It’s one of the few instinctive responses which pop up when we feel most vulnerable, most threatened. This isn’t something Joel can control, or even realises is happening – it’s a defense mechanism, a knee-jerk reaction from deep within designed to keep him safe. I think that’s something we can all relate to. Reaction formation is the process by which you act out the opposite to what you actually feel, in order to avoid confronting those feelings.

When Joel lashes out at Ellie, he is using anger to counteract his internal feelings of relief (that she is safe) and guilt (that she had to put herself in danger for him). Reaction formation is Joel’s favourite defence mechanism, along with compartmentalisation, displacement, and compensation. You can read more about defence mechanisms here. The more these situations occur, the more defensive Joel becomes (showing how much his feelings have grown). His struggle it not anymore with Ellie, but with himself, his own fears and desires, and the cognitive dissonance arising within.

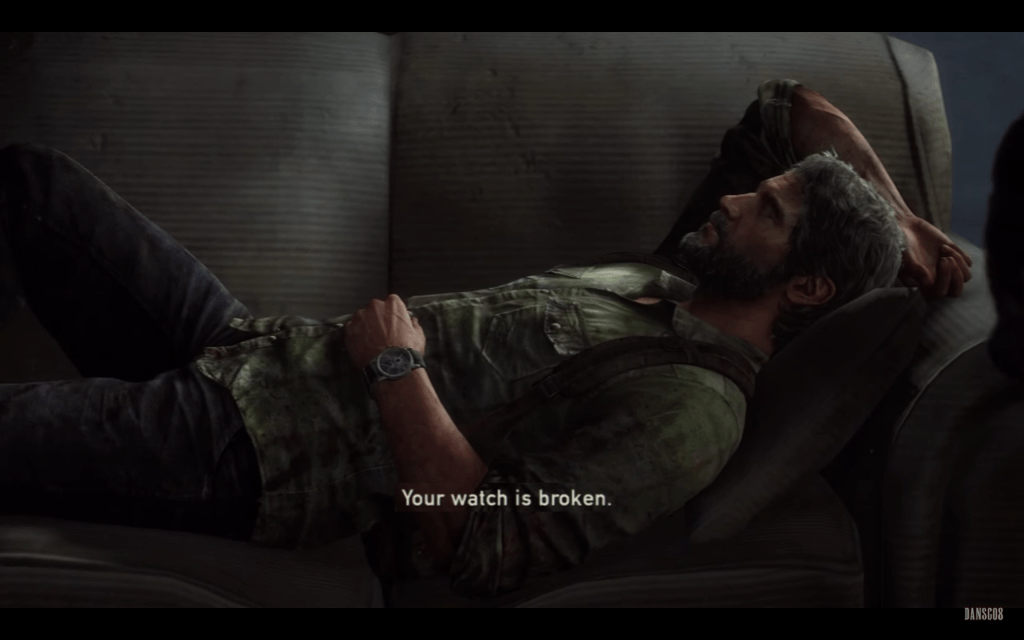

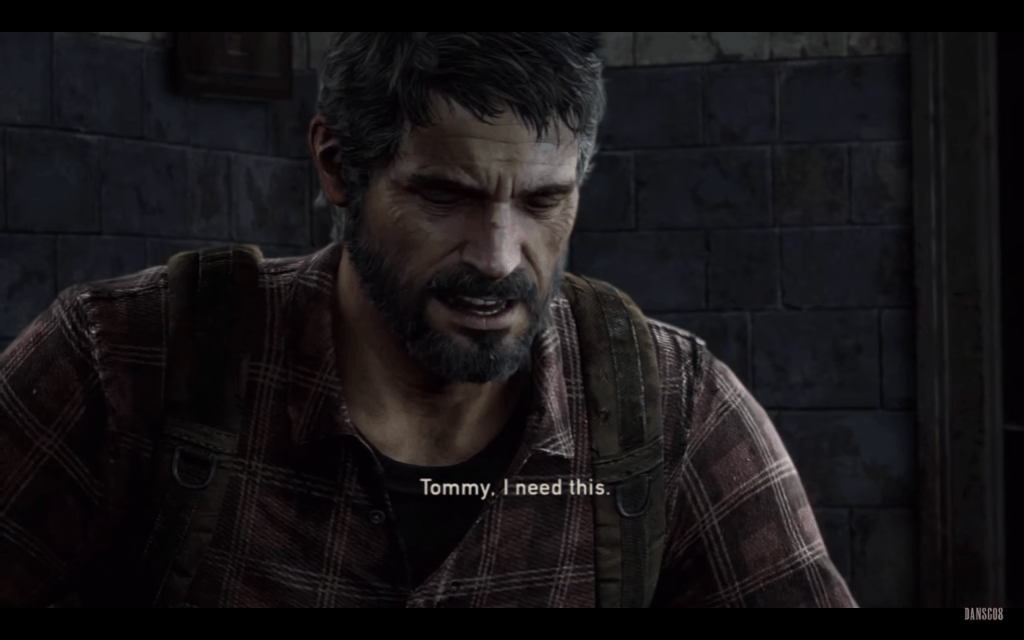

By the time Joel and Ellie get to Tommy’s, they’ve been together for between 4 and 6 months. I’d say it’s pretty tough not to form a bond with someone in this time, even if you are as shut off as Joel. I’d say it’s even harder not to form a bond with a kid. And fortunately for everyone around him, Joel has just about started to admit this to himself.

Joel practically begs Tommy to take Ellie off his hands.

He has acknowledged his emotional bond to her, and is desperately trying to justify ending it. He even says as much.

It catches Tommy off-guard, to the extent he comments on how much Joel has changed: “You still remember how to kill, right?”

After Ellie finds out that Joel is planning on fobbing her off onto Tommy, she does a runner and heads to a cabin in the woods. Joel finds her and dishes out his favourite party trick – emotional displacement and reaction formation. Instead of addressing his fear of losing her, he shouts angrily, “Do you have any idea what your life is worth?”, using her immunity (a fact he didn’t care at all about a few months ago) as a justification for his misplaced rage.

The great thing about Ellie is she calls him out on it. Every time he does some psychological gymnastics to be angry at someone else (think “shot the hell outta that guy” scene) she points it out, and it makes Joel reflect on his behaviour. Usually his most powerful revelations follow a significant conflict, wherein he is forced to face his own demons.

This seems to be the point that Joel (consciously) acknowledges that Ellie reminds him of his daughter. It hurts at first – a lot – and his response is proportional to that hurt. But something odd happens next: instead of doing what would definitely be the best thing for both him and Ellie, and arguably be the easiest thing for him, he just stops fighting. He gives in, and lets her become the daughter he lost.

Now, by all means I don’t think that Joel just lays back and purposefully succumbs to letting Ellie become his surrogate daughter. That happens gradually. What we see here is Joel realising that Ellie cares for him and already relies on him to feel safe and protected. To Joel, abandoning her now is as good as letting her die. He has become a paternal figure for her, so it is easy to step into the role she’s made for him (which is totally not her fault – she’s a kid and the responsibility is on Joel).

Thus we see Joel become vulnerable. And when I use the word “succumb”, I really do mean it. He has resigned himself to letting his subconscious desires rule – the need to have a daughter again. He fought pretty damn hard to try to stop it, but by University, he’s lost. He essentially allows Ellie to become Sarah. And instead of grieving the daughter he lost, Joel replaces her with one he can have.

He needn’t grieve anymore. Ellie has become her now.

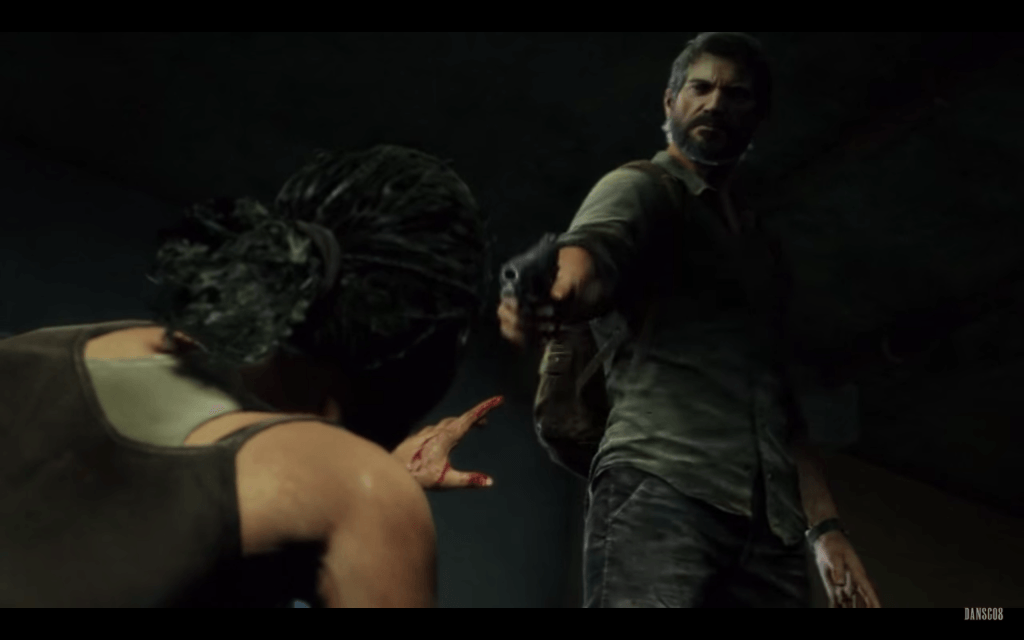

Now that he has made his full transformation into father mode, there is nothing in this world that could get between him and his surrogate daughter. Not even the fate of mankind. Not even her autonomy or, you know, actual choices.

Some players argue that the fireflies didn’t really know Ellie’s brain fungus could save the day and that they should have waited until they could remove it safely. I think given what happens next, that that’s almost a moot point. Objectively what we see is Joel making a decision to kill a lot of people to save Ellie’s life when she had already chosen to die. He maims, tortures and murders strangers with impunity (+/- two unarmed nurses depending on how you chose to experience that scene).

Any shred of fight in him to resist Ellie has completely gone now, and he will do whatever it takes to keep her alive and prevent history from repeating itself.

You’d have to consult with Neil Druckmann to know for sure, but I genuinely believe that Ellie knows Joel is lying in that phenomenal epilogue. Better yet, she’s okay with it. Let’s look at this logically:

Marlene was willing to let Ellie sacrifice herself – even knowing the reasons why, it is never going to be an easy ride to accept the woman who has been the closest thing you ever had to a mother is okay with you dying. That is some seriously damaging rejection. But Joel? Joel was willing to sacrifice the entire human race to keep her alive. When she demands he tell her the truth – I think she is probably testing that love. She’s saying, “Do you really want me around that much?”

If Joel keeps up the facade, it’s much easier for her to justify her own desire to live. They are mutually beneficial here.

Well, kind of. On the one hand, she gets to live and gets to feel loved. On the other, she is literally being used by him as a walking talking breathing memory of his daughter so that he doesn’t have to address his emotions.

It’s dark, morally objectionable, and intellectually challenging. It forces the player to question everything they thought they knew about human character. It forces you to be the bad guy. And it forces you to feel okay that you did it.

Being human is being all. We each have such a magnificent, terrifying, incomprehensible complexity about us. The conflict we feel when we look at Joel is the same as that we feel upon looking at ourselves; believing we have a strong knowledge of right and wrong, Joel shows us we can also sympathise with all those shades of grey in between.

This is something we must all accept – we are a construction, built on pillars of experiences and memories, strengths and vulnerabilities, and additional factors we cannot control or even see. We are not “good” or “bad”, we are a work in progress.